Recent incidents with air traffic controllers have pointed up the hazards of shift work and the supremacy of the circadian rhythm. In one recent case, an air ambulance was forced to land at 2 a.m. without local air traffic controller guidance at Reno-Tahoe International Airport.

These recent incidents have pointed up the existence and causes of what medical science calls Shift Work Sleep Disorder, or SWSD. It’s not clear how many people are affected by SWSD, but it’s probably a fairly significant chunk of the 15% of Americans who perform night-shift work.

When I was 19, I dropped out of school for a time and took a job working in a plant that melted down lead plates from car batteries and turned them into lead ingots. The lead ingots were then sold back to AC Delco and other manufacturers of lead-acid batteries.

My job was to maintain the efficiency of the blast furnace by climbing two stories to its top, where there was a small hole about twice the diameter of a pencil. I’d stick a hollow metal rod inside. On the cooler end of the rod was a hand pump and a toy balloon for collecting the gases. Then I’d bring the balloon back to the lab, rushing so that the entire thing didn’t leak, and run the gases through a chromatograph, an instrument that separated the gases by size. I’d report this to the engineers in the morning. These data would tell the engineers, who wore white hardhats, whether the furnace needed more air, or more fuel, to burn efficiently.

I would scurry along the plant floor, sweating in a hot August summer in Dallas, in a cotton twill uniform which covered me from head to toe, wearing my lab-issue green hardhat, safety goggles, and a breathing mask to protect my lungs from lead dust.

The Dallas summer heat and humidity were made worse by the clothing, the furnace and the tremendous vats of molten lead, perhaps 10 feet from rim to rim. Without warning, the workers on the floor, who wore brown hardhats, would smack their shovels on the surface of the molten lead, beaver-style, sending a spray of brilliant 621°F silver droplets in all directions.

It was how they would haze the new guy in the green hat. They’d laugh as I’d jump backwards in terror. The lead would freeze on contact with the cotton, and no harm was done beyond scaring the crap out of the novice. After the first dozen or so times they did this, I wouldn’t jump, and the game would lose its appeal.

We worked one of two shifts, either 8 am to 8 pm or the opposite, 8 pm to 8 am. Since I had the least seniority, my boss would use me as mortar to fill holes in the schedule that remained after more senior workers had their choices. So, I’d sometimes work days, then after a sleep cycle as short as 36 hours, switch back to nights.

I couldn’t help myself. It would be 4 or 5 a.m. and I had been at work for eight hours or more. Even my 19 year old brain couldn’t take the heat and the hours and the grinding stupidity of the work I was being paid to do. So, I’d put my steel-toed boots up on a table in the lab, lean back in my boss’ chair, and take a nap.

From time to time, one of the other workers would venture into the lab, and would say, “If the boss catches you sleeping on the job, you’ll get fired.” At that point, I honestly didn’t care. I wanted sleep more than I wanted the job.

So I feel a sort of affinity with the air traffic controllers who fall into such a deep sleep alone in the tower at 2 a.m. that they don’t even answer a ringing phone. Regardless of the job, humans need a regular sleep schedule. Without sleep, mistakes get made. On the other hand, if you try to fight your body’s natural cycles, sleep will come anyway.

In general, the more complex the brain, the more likely the animal will need sleep. Dolphins and other cetaceans (sea mammals) with a complex brain and no ability to sleep as we do — quite literally, if you sleep, you die — have adapted a wonderful mechanism where the right hemisphere of the brain goes to sleep, then it awakens and the left hemisphere goes to sleep. (There may be brief periods where both hemispheres sleep.)

Sleep has four stages, conveniently named stage I through stage IV, with stage I being the lightest level and stage IV being the deepest. Night terrors, sleepwalking (somnambulism) and nocturnal enuresis (bedwetting) all occur during stages III and IV of sleep.

There’s another stage, that’s hard to classify as “asleep” or “awake”. It’s something in between. Most people call it Rapid Eye Movement sleep (or REM sleep) and while it has sleep in the name, the only thing it has in common with the other stages of sleep is that the sleeper is not fully responsive to outside events. The eyes move, the brain lights up with activity, and if the REM sleep system didn’t cause us to be paralyzed, we’d be thrashing about. Dogs that smack their flews and whose little paws flick back and forth as though they’re chasing rabbits are in REM sleep, and as far as we know (I’ve asked but received no reply), they really are chasing rabbits in their sleep. REM sleep is dream sleep.

From time to time, patients have an intrusion of the paralysis of REM sleep into the waking world. This is a condition known as narcolepsy which sometimes includes a dramatic paralysis known as cataplexy. For example, fainting goats and people with this condition will suddenly go limp and collapse like a Jenga tower made of Jell-O™ if they are stimulated emotionally. Tell this patient a joke that he thinks is funny, and he’s going down. It sounds like fun and games until you think about what it would be like to live like this.

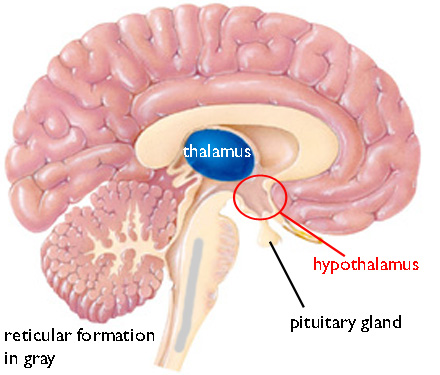

The part of the brain that controls this process is called the reticular formation. “Reticular” means “net-like” and it refers to how this part of the brain looks when it’s stained and examined under a microscope. “Formation” tells us it’s not a tight microscopic cluster of nerve cells, but rather a loose sort of arrangement.

The part of the brain that controls this process is called the reticular formation. “Reticular” means “net-like” and it refers to how this part of the brain looks when it’s stained and examined under a microscope. “Formation” tells us it’s not a tight microscopic cluster of nerve cells, but rather a loose sort of arrangement.

The reticular formation sends its neurotransmitter-laden tendrils all through the brain, extending to every part, releasing the chemicals that make one awake or the ones that put us to sleep. In this way, sleep-wake cycles are coordinated. If a tiger nibbles on our toe, or a window breaks downstairs, the sensory systems are tasked with sending that information to the reticular formation, which like Paul Revere gallops along the streets and alleys of our brain, sending the alarm.

The hypothalamus is a part of the brain that regulates homeostatic loops, the daily housekeeping chores that keep the body’s temperature, water content, energy reserves, and most everything else at normal levels.

The old psychology class joke is that the hypothalamus mediates the “four Fs”: feeding, fighting, fleeing and mating.

A small part of the hypothalamus called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), no bigger than the head of a map pin, is responsible for keeping track of light/dark cycles. The reticular formation and the hypothalamus work together in tandem to keep the normal cycle of circadian rhythms.

If a human is left to his own devices — for example, if he lives in a cave with no external cues for a long period of time — he tends to adopt a sleep-wake cycle that repeats about every 25 hours or so. This is what’s called a circadian rhythm. Depending on who you ask, “circa” refers to either the “around” aspect of the day, as in “around the clock” or to the “about” aspect, as in “not-quite-24-hours”. “Dia”, of course, is Latin for “day”.

Our circadian rhythms are altered, or even reset, by what are called zeitgeibers, German for “time givers”. The sun rising, the buzz of traffic, the hustle and bustle of errands are all examples of external zeitgebers in our everyday lives. The problem with night shift work is that an individual’s internal and external zeitgebers. For example, if you have children, the school day may run from 7:30 am to 3:30 pm regardless of what hours your boss expects you to work.

Maybe persons who are prone to shift work sleep disorder (SWSD) have a greater degree of conflict between external and internal zeitgebers, or problems with one or the other zeitgeber circuit. Certainly, some people are more affected than others, a point which has caused some to doubt the existence of SWSD as an entity. Unless you deny the effect of the brain on behavior, however, it’s hard to resolve this worldview with what we see all around us.

What are the chemicals that act as the Paul Reveres and Sandmen of the brain, alerting us to danger or putting us to sleep when there is none? The Greek word orexia means “longing” or “desire”. Patients with anorexia nervosa, for example, have no desire or longing for food (an- + -orexia) because of a disorder of the nervous system (nervosa). Orexins are a class of chemicals, found in the hypothalamus, that are thought to regulate behaviors.

Orexins are also called hypocretins, and hypocretin-1 and hypocretin-2 regulate sleep, appetite, and energy usage. Damaging the gene which codes for the hypocretin receptor (the protein found on the cell surface that responds to the hypocretin signal) causes narcolepsy in dogs, mice and possibly humans. Scientists also believe that hypocretin is the link between sleep and obesity. If the hypocretin-making neurons die, mice eat too much and become fat. It is well-known that disturbances in sleep cycles can make obesity worse. Maybe these chemicals are the link.

Circadian rhythms dominate almost all aspects of life — and death. For example, heart attacks and strokes peak at 10 a.m. Most surgeons believe that patients have better surgical outcomes if the surgery is performed early in the morning. Whether or not this has to do with the surgeon or the patient or both, we don’t know. For example, liver transplantation complications are more than twice as likely to occur in the evening than other times of day. However, the time of day may not matter in elective heart surgeries. It may depend on the organ or the personality of doctors and nurses who go into (say) liver transplantation versus heart surgery.

Or, it might be the patients who undergo liver transplants are different than the patients who undergo coronary artery bypass surgery. People are different. Some are more prone to SWSD than others. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist, or that we can afford to ignore it. In many cases, our lives depend on good science.