As a neuroscientist and dog trainer, I’ve always been fascinated by the interface between the two.

For me, the most powerful forms of dog training utilize the secret bonds of empathy and guidance, much like a psychiatrist will act as docent to take a patient on a guided tour of their own brain.

For example, in the therapeutic school called Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, the therapist acts as neuroscientist, suggesting hypotheses and carrying out experiments in conjunction with the patient. “Let’s hypothesize that you will be harmed by snakes, Mr. Jones. Are you saying that all snakes are harmful, or just some types?”

For example, in the therapeutic school called Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, the therapist acts as neuroscientist, suggesting hypotheses and carrying out experiments in conjunction with the patient. “Let’s hypothesize that you will be harmed by snakes, Mr. Jones. Are you saying that all snakes are harmful, or just some types?”

That’s how good, effective dog training works, as well. I have always been drawn to the power and elegance of the very best behavioral-based trainers, such as Dr. Sophia Yin, Monique Anstee and Dr. Suzanne Hetts.

(Video of how Monique makes this work for her and her partner Basil.)

Force-based methods, or methods based on half-baked “theories” like dominance theory, look great on TV but don’t work and may well do significant harm to dogs, just as they would to humans. Ethical, behavioral-based therapies may not work, but they won’t hurt your dog, or your relationship with your dog.

I’m interested in how dog brains work, in the same way a human therapist might be interested in how human brains work.

One open question — and likely a completely unanswerable one — is how dogs’ brains got that way. (For fun after-dinner conversation, or for blogs, nothing is better than an unanswerable question.)

Genetic evidence suggests that dogs were domesticated independently at several different locations at about the same time. Dog domestication probably happened about 32,000 years ago. Paleoanthropologist Pat Shipman believes that dogs were first raised as hunting tools, then became companions and even food in very lean times.

If this is true, it means that dogs and cats were the first animals domesticated for humans as a tool to act at a distance. Some animals were for food. Others were tools used to pull a sled or a plow.

Raptors and carrier pigeons act at a distance, but were used much later and without much domestication. Falconry appeared about 3000 years before present (YBP) and carrier pigeons were developed about the same time.

Dogs and cats could work semi-independently, increasing the range over which a human could act to as much as several hundred meters. Like the atlatl and bow and arrow, both developed in the same range of human prehistory (about 40,000 YBP), dogs and cats allowed prehistoric humans to exert action at a distance. This would be a tremendous advantage over having to (say) club a woolly mammoth to death with a stone ax.

Dogs would have been raised for their ability to work with humans hunting in packs, for example cutting a weak animal from a herd of buffalo so that humans could bring it down and kill it. The dogs would get the entrails and bones as food, and the humans would butcher the animal for the part the dogs were less interested in, such as the muscles and hide.

The story for cats would be different. In the eternal struggle between humans and rodents — rodents always stealing and spoiling human food, causing disease and starvation — humans have only recently gained the upper hand. The enslavement of rats and mice as research animals is their race’s penance for the original sin of starving my ancestors and killing them with biowarfare agents such as the bubonic plague.

Cats would be the roving secret agents in the war on rodents, allowed to operate independently with minimal supervision.

Dogs, on the other hand, would be allowed to live in close proximity with humans, even sleeping with them. Dogs who could “read” their masters and could work as a brainy tool at a distance would be prized. We see this as the dog sports of obedience, herding and agility to this day. Each of these sports consists of utilizing the invisible leash between humans and dogs to spectacular and pleasing effect.

(For wonderful still images of dogs herding, see Jeff Jaquish’s Flickr page. For books about dog agility, including mine, see Cleanrun.)

Early genetic evidence suggested that dogs were developed in East Asia. More recent studies suggest that another location, perhaps the Middle East, is the most likely origin. Others have argued for domestication at about the same time in multiple locations. Genetic studies are complicated by the ability of wolves to interbreed with domestic dogs, although there are no native wolves anywhere near some of the supposed domestication sites.

What were the ur-dogs? vonHoldt et al. argue based on the genetic evidence that they resembled the modern breeds of: basenji, Afghan hound, Samoyed, saluki, Canaan dog, New Guinea singing dog, dingo, chow chow, Chinese Shar Pei, Akita, Alaskan malamute, Siberian husky and American Eskimo dog. This makes sense both based on the genetics of these dogs, but also the many uses of domesticated dogs. For example, the dingo and its cross with a now-disappeared British herding dog, the Smithfield, produced the Australian Cattle Dogs pictured above. As you look down this list, you see “alarm” dogs, protection dogs, livestock management dogs, and sled-pulling dogs. This probably points to the reasons for domestication.

This also supports Shipman’s theory that dogs were working tools before they were food, since there seems to be more diversity based on working style than on body type.

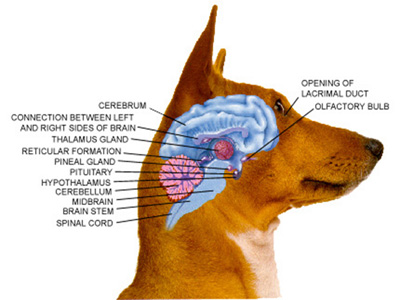

What did domestication do to the dog’s brain? A number of years ago, a friend and colleague who studies the prefrontal cortex — the part of the brain where our “mothers” live, responsible for “conscience” and social behavior — made a provocative statement at her seminar. Grazyna Rajkowska said based on fossil cast evidence, “dogs and cats started with the same amount of prefrontal cortex,” but through domestication, dogs developed a prefrontal cortex while cats did not.

What did domestication do to the dog’s brain? A number of years ago, a friend and colleague who studies the prefrontal cortex — the part of the brain where our “mothers” live, responsible for “conscience” and social behavior — made a provocative statement at her seminar. Grazyna Rajkowska said based on fossil cast evidence, “dogs and cats started with the same amount of prefrontal cortex,” but through domestication, dogs developed a prefrontal cortex while cats did not.

She was referring to studies by Leonard Radinsky that correlated hunting behavior in canids with the development of various brain regions. Since brains don’t survive the fossilization process, paleontologists are forced to infer the structure of the brain from the skull that surrounds it. This works pretty well because the inside surface of the skull is soft in infants and is partially molded by the development of the brain. Radinsky sadly died at the age of 48, so he’s not here to defend himself, but I will try to do justice to his work.

She was referring to studies by Leonard Radinsky that correlated hunting behavior in canids with the development of various brain regions. Since brains don’t survive the fossilization process, paleontologists are forced to infer the structure of the brain from the skull that surrounds it. This works pretty well because the inside surface of the skull is soft in infants and is partially molded by the development of the brain. Radinsky sadly died at the age of 48, so he’s not here to defend himself, but I will try to do justice to his work.

Radinsky focused on the prorean gyrus (Greek πρωρα + Latin gyrus) a bump (gyrus) that resembled the prow of a ship (πρωρα, prora) to some early neuroanatomist. The brains of pack-hunting animals have a larger prorean gyrus than the brains of ancestral canids (dog-like animals) and felids (cat-like animals). Here’s the prorean gyrus in a dog brain:

The prorean gyrus in the dog's brain. Base image: http://vanat.cvm.umn.edu/grossbrain/Pages/BrDivPgs/BrDgLat3.html

Hunting carnivores — dogs and wolves and their ancestors — have a much larger prorean gyrus. Thus, we guess that much of the circuitry needed for hunting behavior is located in the prorean gyrus.

This would include watching other members of the pack (or, later, your human master); watching the prey and the prey’s cohorts; and knowing, without checking, exactly how to modify your attack based on what you see, smell and hear. It’s really a great example of how complicated behaviors can be packed into a relatively small amount of brain real estate.

Radinsky’s findings are consistent with more recent scientific evidence. Roberts, McGreevy and Valenzuela published a study last year in PLoS One that showed how domestication has changed the anatomy of the dog brain. It’s well-known that dolichocephalic dogs (such a greyhound) are much better lure coursers and hunters than brachycephalic dogs (such as a spaniel).

Brachycephalic dogs (let’s call them “round-headed”) have a brain that is rotated and the olfactory lobe is displaced upward. The correlation between round-headedness (measured by the cephalic index) and upward displacement of the olfactory lobe is quite strong, with a correlation (r) of 0.971. This means that about 94% of the variation in olfactory lobe position is explained by the cephalic index, and vice-versa.

As Roberts et al. put it (p. e11946):

Because differences in cranial morphology across dog breeds were closely associated with major neuroanatomical changes, whether these also lead to differences in behavior is a major open question.

It’s provocative, isn’t it? The exact area where domesticated dog brains seem to have changed the most, the prorean gyrus, is exactly where human social behavior (“manners”) tend to reside in the human brain, where brains got bigger in dog-like ancestors that hunt for a living, and where the biggest changes occurred in the domestication of the dog.

It’s time we changed the old joke, “Dogs have owners, cats have staff” to “Dogs have a prorean gyrus, cats don’t.” Okay, so maybe I need to work on that.

For those interested in this topic, I highly recommend the book Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History by Wang X and Tedford RH. I downloaded it to my iPad while working on this article. I love this modern world.

Thanks to Tracy Smith and Rosemary Hoffman for comments leading to critical edits in the human prehistory and tools section.